Kristin L. Andrejko 1 ,2, *; Jake M. Pry, PhD 2, *; Jennifer F. Myers, MPH 2 ; Nozomi Fukui 2 ; Jennifer L. DeGuzman, MPH 2 ; John Openshaw, MD 2 ; James P. Watt, MD 2 ; Joseph A. Lewnard, PhD 1 ,3 ,4 ; Seema Jain, MD 2 ; California COVID-19 Case-Control Study Team (View author affiliations)

What is already known about this topic?

Face masks or respirators (N95/KN95s) effectively filter virus-sized particles in laboratory settings. The real-world effectiveness of face coverings to prevent acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 infection has not been widely studied.

What is added by this report?

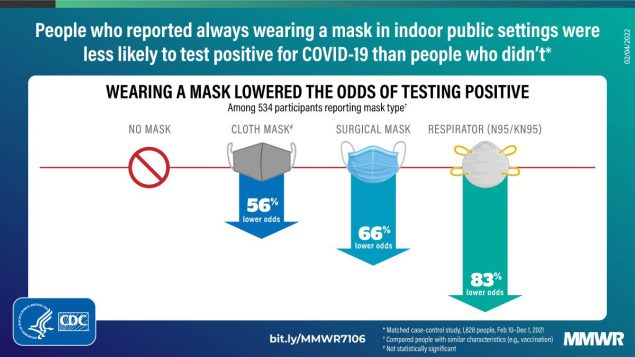

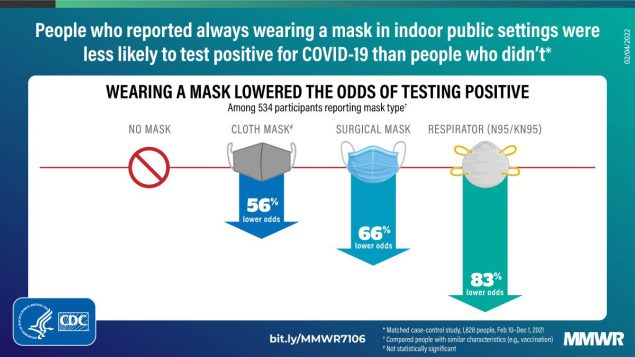

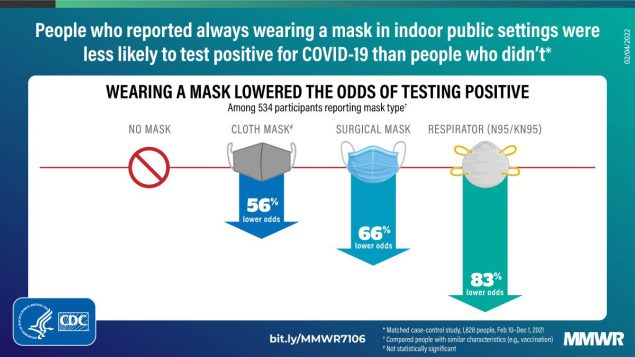

Consistent use of a face mask or respirator in indoor public settings was associated with lower odds of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result (adjusted odds ratio = 0.44). Use of respirators with higher filtration capacity was associated with the most protection, compared with no mask use.

What are the implications for public health practice?

In addition to being up to date with recommended COVID-19 vaccinations, consistently wearing a comfortable, well-fitting face mask or respirator in indoor public settings protects against acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 infection; a respirator offers the best protection.

Article MetricsViews equals page views plus PDF downloads

Tables Related Materials

The use of face masks or respirators (N95/KN95) is recommended to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 (1). Well-fitting face masks and respirators effectively filter virus-sized particles in laboratory conditions (2,3), though few studies have assessed their real-world effectiveness in preventing acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 infection (4). A test-negative design case-control study enrolled randomly selected California residents who had received a test result for SARS-CoV-2 during February 18–December 1, 2021. Face mask or respirator use was assessed among 652 case-participants (residents who had received positive test results for SARS-CoV-2) and 1,176 matched control-participants (residents who had received negative test results for SARS-CoV-2) who self-reported being in indoor public settings during the 2 weeks preceding testing and who reported no known contact with anyone with confirmed or suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection during this time. Always using a face mask or respirator in indoor public settings was associated with lower adjusted odds of a positive test result compared with never wearing a face mask or respirator in these settings (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.44; 95% CI = 0.24–0.82). Among 534 participants who specified the type of face covering they typically used, wearing N95/KN95 respirators (aOR = 0.17; 95% CI = 0.05–0.64) or surgical masks (aOR = 0.34; 95% CI = 0.13–0.90) was associated with significantly lower adjusted odds of a positive test result compared with not wearing any face mask or respirator. These findings reinforce that in addition to being up to date with recommended COVID-19 vaccinations, consistently wearing a face mask or respirator in indoor public settings reduces the risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection. Using a respirator offers the highest level of personal protection against acquiring infection, although it is most important to wear a mask or respirator that is comfortable and can be used consistently.

This study used a test-negative case-control design, enrolling persons who received a positive (case-participants) or negative (control-participants) SARS-CoV-2 test result, from among all California residents, without age restriction, who received a molecular test result for SARS-CoV-2 during February 18–December 1, 2021 (5). Potential case-participants were randomly selected from among all persons who received a positive test result during the previous 48 hours and were invited to participate by telephone. For each enrolled case-participant, interviewers enrolled one control-participant matched by age group, sex, and state region; thus, interviewers were not blinded to participants’ SARS-CoV-2 infection status. Participants who self-reported having received a previous positive test result (molecular, antigen, or serologic) or clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 were not eligible to participate. During February 18–December 1, 2021, a total of 1,528 case-participants and 1,511 control-participants were enrolled in the study among attempted calls placed to 11,387 case- and 17,051 control-participants (response rates were 13.4% and 8.9%, respectively).

After obtaining informed consent from participants, interviewers administered a telephone questionnaire in English or Spanish. All participants were asked to indicate whether they had been in indoor public settings (e.g., retail stores, restaurants or bars, recreational facilities, public transit, salons, movie theaters, worship services, schools, or museums) in the 14 days preceding testing and whether they wore a face mask or respirator all, most, some, or none of the time in those settings. Interviewers recorded participants’ responses regarding COVID-19 vaccination status, sociodemographic characteristics, and history of exposure to anyone known or suspected to have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the 14 days before participants were tested. Participants enrolled during September 9–December 1, 2021, (534) were also asked to indicate the type of face covering typically worn (N95/KN95 respirator, surgical mask, or cloth mask) in indoor public settings.

The primary analysis compared self-reported face mask or respirator use in indoor public settings 14 days before SARS-CoV-2 testing between case- (652) and control- (1,176) participants. Secondary analyses accounted for consistency of face mask or respirator use all, most, some, or none of the time. To understand the effects of masking on community transmission, the analysis included the subset of participants who, during the 14 days before they were tested, reported visiting indoor public settings and who reported no known exposure to persons known or suspected to have been infected with SARS-CoV-2. An additional analysis assessed differences in protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection by the type of face covering worn, and was limited to a subset of participants enrolled after September 9, 2021, who were asked to indicate the type of face covering they typically wore; participants who indicated typically wearing multiple different mask types were categorized as wearing either a cloth mask (if they reported cloth mask use) or a surgical mask (if they did not report cloth mask use). Adjusted odds ratios comparing history of mask-wearing among case- and control-participants were calculated using conditional logistic regression. Match strata were defined by participants’ week of SARS-CoV-2 testing and by county-level SARS-CoV-2 risk tiers as defined under California’s Blueprint for a Safer Economy reopening scheme. † Adjusted models accounted for self-reported COVID-19 vaccination status (fully vaccinated with ≥2 doses of BNT162b2 [Pfizer-BioNTech] or mRNA-1273 [Moderna] or 1 dose of Ad.26.COV2.S [Janssen (Johnson & Johnson)] vaccine >14 days before testing versus zero doses), household income, race/ethnicity, age, sex, state region, and county population density. Statistical significance was defined by two-sided Wald tests with p-values

A total of 652 case- and 1,176 control-participants were enrolled in the study equally across nine multi-county regions in California ( Table 1). The majority of participants (43.2%) identified as non-Hispanic White; 28.2% of participants identified as Hispanic (any race). A higher proportion of case-participants (78.4%) was unvaccinated compared with control-participants (57.5%). Overall, 44 (6.7%) case-participants and 42 (3.6%) control-participants reported never wearing a face mask or respirator in indoor public settings ( Table 2), and 393 (60.3%) case-participants and 819 (69.6%) control-participants reported always wearing a face mask or respirator in indoor public settings. Any face mask or respirator use in indoor public settings was associated with significantly lower odds of a positive test result compared with never using a face mask or respirator (aOR = 0.51; 95% CI = 0.29–0.93). Always using a face mask or respirator in indoor public settings was associated with lower adjusted odds of a positive test result compared with never wearing a face mask or respirator (aOR = 0.44; 95% CI = 0.24–0.82); however, adjusted odds of a positive test result suggested stepwise reductions in protection among participants who reported wearing a face mask or respirator most of the time (aOR = 0.55; 95% CI = 0.29–1.05) or some of the time (aOR = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.35–1.46) compared with participants who reported never wearing a face mask or respirator.

Wearing an N95/KN95 respirator (aOR = 0.17; 95% CI = 0.05–0.64) or wearing a surgical mask (aOR = 0.34; 95% CI = 0.13–0.90) was associated with lower adjusted odds of a positive test result compared with not wearing a mask ( Table 3). Wearing a cloth mask (aOR = 0.44; 95% CI = 0.17–1.17) was associated with lower adjusted odds of a positive test compared with never wearing a face covering but was not statistically significant.

During February–December 2021, using a face mask or respirator in indoor public settings was associated with lower odds of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection, with protection being highest among those who reported wearing a face mask or respirator all of the time. Although consistent use of any face mask or respirator indoors was protective, the adjusted odds of infection were lowest among persons who reported typically wearing an N95/KN95 respirator, followed by wearing a surgical mask. These data from real-world settings reinforce the importance of consistently wearing face masks or respirators to reduce the risk of acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 infection among the general public in indoor community settings.

These findings are consistent with existing research demonstrating that face masks or respirators effectively filter viruses in laboratory settings and with ecological studies showing reductions in SARS-CoV-2 incidence associated with community-level masking requirements (6,7). While this study evaluated the protective effects of mask or respirator use in reducing the risk the wearer acquires SARS-CoV-2 infection, a previous evaluation estimated the additional benefits of masking for source control, and found that wearing face masks or respirators in the context of exposure to a person with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with similar reductions in risk for infection (8). Strengths of the current study include use of a clinical endpoint of SARS-CoV-2 test result, and applicability to a general population sample.

The findings in this report are subject to at least eight limitations. First, this study did not account for other preventive behaviors that could influence risk for acquiring infection, including adherence to physical distancing recommendations. In addition, generalizability of this study is limited to persons seeking SARS-CoV-2 testing and who were willing to participate in a telephone interview, who might otherwise exercise other protective behaviors. Second, this analysis relied on an aggregate estimate of self-reported face mask or respirator use across, for some participants, multiple indoor public locations. However, the study was designed to minimize recall bias by enrolling both case- and control-participants within a 48-hour window of receiving a SARS-CoV-2 test result. Third, small strata limited the ability to differentiate between types of cloth masks or participants who wore different types of face masks in differing settings, and also resulted in wider CIs and statistical nonsignificance for some estimates that were suggestive of a protective effect. Fourth, estimates do not account for face mask or respirator fit or the correctness of face mask or respirator wearing; assessing the effectiveness of face mask or respirator use under real-world conditions is nonetheless important for developing policy. Fifth, data collection occurred before the expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant, which is more transmissible than earlier variants. Sixth, face mask or respirator use was self-reported, which could introduce social desirability bias. Seventh, small strata limited the ability to account for reasons for testing in the adjusted analysis, which may be correlated with face mask or respirator use. Finally, this analysis does not account for potential differences in the intensity of exposures, which could vary by duration, ventilation system, and activity in each of the various indoor public settings visited.

The findings of this report reinforce that in addition to being up to date with recommended COVID-19 vaccinations, consistently wearing face masks or respirators while in indoor public settings protects against the acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 infection (9,10). This highlights the importance of improving access to high-quality masks to ensure access is not a barrier to use. Using a respirator offers the highest level of protection from acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 infection, although it is most important to wear a well-fitting mask or respirator that is comfortable and can be used consistently.

Yasmine Abdulrahim, California Department of Public Health; Camilla M. Barbaduomo, California Department of Public Health; Julia Cheunkarndee, California Department of Public Health; Miriam I. Bermejo, California Department of Public Health; Adrian F. Cornejo, California Department of Public Health; Savannah Corredor, California Department of Public Health; Najla Dabbagh, California Department of Public Health; Zheng N. Dong, California Department of Public Health; Ashly Dyke, California Department of Public Health; Anna T. Fang, California Department of Public Health; Diana Felipe, California Department of Public Health; Paulina M. Frost, California Department of Public Health; Timothy Ho, California Department of Public Health; Mahsa H. Javadi, California Department of Public Health; Amandeep Kaur, California Department of Public Health; Amanda Lam, California Department of Public Health; Sophia S. Li, California Department of Public Health; Monique Miller, California Department of Public Health; Jessica Ni, California Department of Public Health; Hyemin Park, California Department of Public Health; Diana J. Poindexter, California Department of Public Health; Helia Samani, California Department of Public Health; Shrey Saretha, California Department of Public Health; Maya Spencer, California Department of Public Health; Michelle M. Spinosa, California Department of Public Health; Vivian H. Tran, California Department of Public Health; Nikolina Walas, California Department of Public Health; Christine Wan, California Department of Public Health; Erin Xavier, California Department of Public Health.